Special Report

By Mustafa Fetouri

ACCORDING TO the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 4 million of Libya’s estimated population of 6.5 million people will face serious water shortages. Like many other countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, Libya ranks high on the water scarcity index. It is one of the driest countries in a region that is home to 11 of the 15 driest countries in the world. Pundits and analysts have long predicted that the next regional war could well be about water.

The World Resources Institute projects that Libya, by 2040, will suffer from severe water stress, which is a measure of the water withdrawal against the available renewable quantities of surface and underground water. If the country does not take any immediate measures to tackle the problem, it could get worse; desertification could become an even more serious problem than it is now as more land is cleared for ever-expanding cities without any green belt around them to hold the desert back.

Rain is almost negligible in Libya, coming in late winter and early spring in quick downpours lasting only minutes at a time. Making the situation worse is the absence of running rivers. Yet Libya today has more water security than many of its neighbors.

Tunisia, for example, imposed water rationing last April by cutting water for at least seven hours every night. Algeria faces the same problem, while Egypt worries about the consequences of Ethiopia’s dam on the River Nile which provides Egypt’s only water sources.

Libya’s water deficit has many contributors: low annual rainfall, climate change, harsh desert climate, rising demand, water misuse, aging pipeline networks and lack of investment in water resources. Industrial and agricultural water demand, coupled with the increase in population numbers, have further exacerbated the problem.

WHAT HAS BEEN DONE?

Libya’s water shortages go back to the 1930s while the country was under Italian occupation (1911–1945) but lack of resources and finances made it difficult to solve. All that changed when oil companies started drilling for oil in the early 1960s and found water in abundance. But all underground aquifers were found deep in the desert and hundreds of miles away from the population centers along the Mediterranean coast in the north where most Libyans live.

How best to make use of such a precious commodity was the main question facing successive Libyan governments. In the early 1970s, the state brought in international experts to study the feasibility and economic cost of building a man-made river to transport water from the southern regions to the north where it is most needed.

CREATING A RIVER

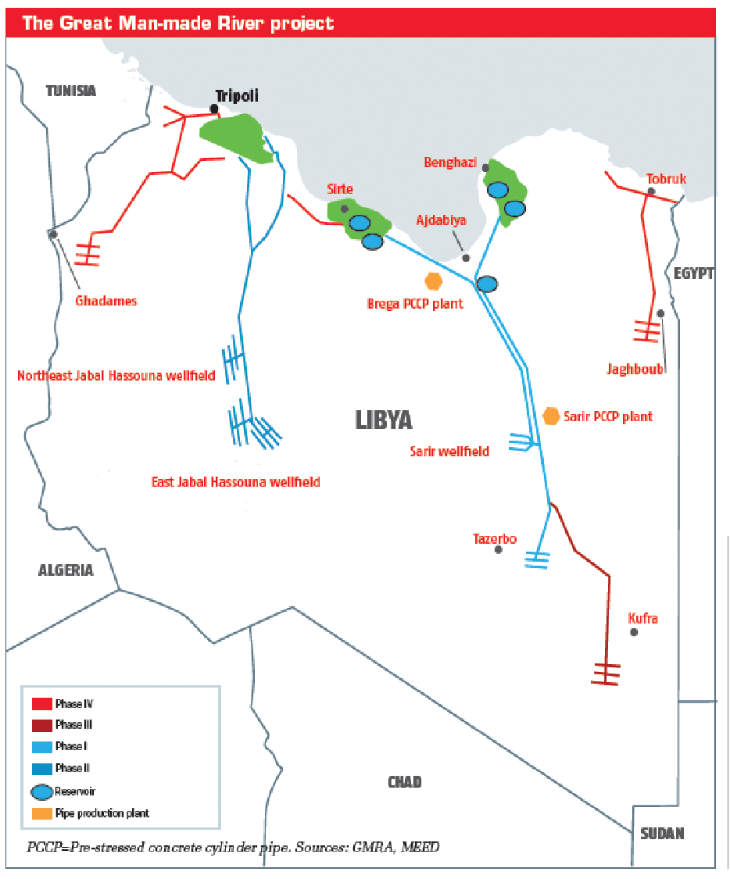

When the idea of the Great Man-Made River (GMMR) was first floated in the 1970s—entailing the construction of a network of pipelines to transport water across thousands of kilometers—it sounded like a crazy idea. Nevertheless, Colonel Muammar Qaddafi decided to launch the project in 1983. The timing was hardly conducive. Libya’s international relations were in shambles. The country was under U.S. sanctions including export bans of some technologies and a ban of oil exports, the main source of Libya’s revenue. Libya could not even enlist the help of private American contractors. Because Qaddafi was considered an international pariah by the West, Libya’s access to international financial markets to finance such a huge project was severely limited.

But the water problem was growing by the day and sea water was already seeping into local wells, compromising the drinking water. Qaddafi went ahead with the project, which he called the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” To locally raise the estimated $30 billion needed to fund the project, the government raised taxes on luxury goods including tobacco and air travel. Even imported bananas were considered a “luxury” and were taxed at a higher rate.

Great Man-Made River Facts

GMMR is considered the biggest irrigation project in the world. It pumps some 6.5 million cubic meters of fresh water every day, providing drinking water to nearly 7 million people. It was designed to irrigate some 400,000 acres of desert to make Libya agriculturally self-sufficient and a regional producer.

Water comes from 13,000 wells with a depth of 500 meters drilled deep in the desert hundreds of kilometers away, tapping into huge underground Nubian Sandstone Aquifer lakes. Four-meter-wide pipes made from pre-stressed concrete run across more than 2,800 kilometers now; when completed it would cover most of the country.

Water is collected in at least ten open and underground reservoirs before being pumped into local networks in cities, towns and farmlands nearby. Omar Mukhtar and Al-Gardabia are the two main reservoirs and have become tourist attractions.

GMMR water is cheap compared to desalinated water. Experts estimated that one liter of water costs only 10 percent of the cost of desalinated seawater. Based on 2007 retrieval rates, the GMMR could secure the water needs for the country for the next 1,000 years. Others have warned that the water might run out in 100 years.

The project was divided into four stages, each with target water delivered volumes and each with its own time scale from start to end. Only phases I and II have been completed while phase III is only partially operational and phase IV is yet to be finished. Most of the remaining work has to do with sub-connections, making water available to more remote areas deep in the country’s interior. No new wells are planned nor are any new massive pipes to be connected, as the main river body is already complete.

Some 13,000 water wells were drilled, and a plant was built to produce the pre-stressed concrete pipes. These pipes would be the backbone of the network sprawling across Libya covering nearly one third of its surface area. The entire project cost Libya a staggering $30 billion, but it was money well spent: the country’s water problem was solved at less cost than the alternative solution (desalination plants), and the country was able to avoid international borrowing, which would have been available only at prohibitive rates.

Libya addressed one domestic problem but found that it was in the crosshairs of the international community. Accused of supporting international terrorism by the United States and its allies, Qaddafi was further accused of attempts to produce chemical and biological weapons. TIME magazine ran a three-page article in its exclusive April 1996 issue in which it claimed that Libya was digging under the Tarhouna Mountains, southwest of Tripoli, to build a chemical weapons plant. In fact, the excavation was intended to bury GMMR’s huge pipelines supplying water to the capital. Washington Report’s late publisher, Andrew I. Killgore, personally visited the place to dispel that story (see pp. 56-57, March 2001 Washington Report). The TIME article quoted CIA Director John Deutch as saying that Libya was building what he called “the world’s largest underground chemical-weapons plant.” In September of the same year Jane’s Defense Weekly published an article titled “Qaddafi Tunnels Into Trouble both Within and Without.” To date neither publication has apologized for the error or issued a correction.

In August 2022, Washington’s Middle East Institute published a study that cast doubt on the economic feasibility of the GMMR even though it started supplying water to Benghazi, in the east, in 1991 when phase I was completed and to Tripoli in 1996.

Today, GMMR provides 70 percent of fresh water to Libyans, from the Egyptian borders in the east to the Tunisian borders in the northwest. The ultimate aim was to transform the country’s mostly desert terrain to blooming fertile land producing everything from wheat to all kinds of fruits and vegetables. Indeed hundreds of farms were developed in once desert land and most of them were handed over to farmers at a fraction of their cost.

GMMR TODAY

Eleven years after Qaddafi’s assassination, his main legacies, including GMMR, are suffering the many consequences of the NATO-supported rebellion that ended his rule. The entire project’s infrastructure is under threat. Political instability, negligence, illegal connections to its pipelines and badly maintained water networks are among the biggest problems. In July 2011 NATO bombed the biggest pipe-making plant at Brega, in eastern Libya, killing six of the facility’s security guards. In a press release the alliance claimed it was responding to ground fire coming from the facility.

Even worse, the GMMR has occasionally been used as a weapon against certain areas of the country; fighting militias cut water flow to areas controlled by their rivals.

Financial corruption is also depriving the project from enough funds to expand and maintain its infrastructure. GMMR managers report that overall supervision and security during Qaddafi’s rule was much better than it is today. Personally committed to the project, Qaddafi had a habit of making unannounced visits to different sites and to the management headquarters to inspect operations for himself. Maintaining a stable power supply has also become another problem as power cuts are frequent.

Post-Qaddafi Libya has been failing on almost every level but it cannot afford to fail when it comes to providing water to its people. GMMR should be prioritized in state budgeting, and intercity water connections must be modernized as quickly as possible to end leaks. The country also should pass stricter anti-sabotage laws to protect GMMR. Furthermore, GMMR should have its own power stations, ending its dependence on the already decaying power network and outdated power stations.

As Libya earns more money producing more oil (current production is about 1.2 million barrels a day) and the cost of desalination is decreasing, the government should consider launching desalination plants. This would relieve the pressure on GMMR and help Libya reserve water for larger scale agriculture projects to turn the country into a regional agriculture producer. But such policies require political stability, leadership and political will—all of which are lacking in Libya today.

Mustafa Fetouri is a Libyan academic and freelance journalist. He received the EU’s Freedom of the Press prize. He has written extensively for various media outlets on Libyan and MENA issues. He has published three books in Arabic. His email is mustafafetouri@hotmail.com and Twitter: @MFetouri.